By Anne Dealy, Director of Education and Public Information

This year

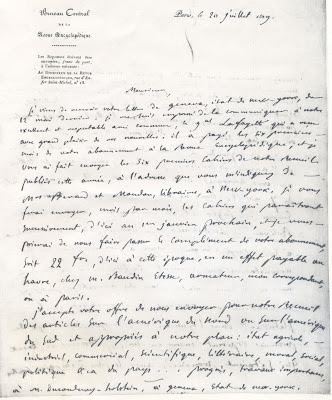

in Geneva United States Rose Hill Mansion

According

to Priscilla Brewer’s book From Fireplace

to Cookstove: Technology and the Domestic Ideal, most early Americans

followed the English example, heating their homes with fireplaces. The biggest

drawback to fireplaces, then as now, is that most of the fire’s heat escapes

through the chimney. Sitting by the fire meant a comfortable front and a cold

backside. In northern European countries like Holland

and Germany Europe ,

where wood was scarce and costly by this time. For several reasons, including

their milder climate, the English did not embrace this new technology,

preferring “the cheerful flicker…of a fire” (Brewer, p. 24). The frontier

colonists in America North America were rarely warm in winter, and families

confined themselves to one or two rooms for the long cold winters.

Brewer

indicates that in 1800 the typical American family burned 18-20 cords of

firewood a year to heat their home. Inhabiting a country rich in forested land,

Americans used up wood at rates that shocked Europeans. In newly settled areas,

there was so much wood and so few people to clear it that wasteful practices

became the norm. Wanting to clear land quickly, settlers often burned forests,

ridding themselves of the trees and producing potash, a valuable compound used

as a fertilizer and in the manufacture of glass. Geneva New York

1806 Geneva

Unfortunately,

these practices quickly led from abundance to scarcity, with settled areas of

the colonies experiencing fuel shortages as early as the 1680s. By the mid-1700s

the fuel crisis was acute in some areas, and the high price of wood led some

Americans, including Benjamin Franklin, to consider ways to heat homes more

efficiently. In order to accommodate the English desire for an open hearth and

visible fire, Franklin and other focused on improving the efficiency of the

fireplace. His 1741 solution was the Franklin stove. This “stove” was really a

cross between a stove and a fireplace. It was essentially a metal box, open on

one side, which fit into a fireplace and increased the radiation of the fire’s

heat into a room. You can see a late 19th-century colonial revival

variation on this design in the rear parlor at Rose Hill Mansion

“Franklin”

Stove at Rose Hill

The

prejudice against enclosed stoves was slow to die, with critics arguing that

warm, stuffy air promoted sickness and that stoves were unrefined. Of greater

consideration for most families was the high cost of purchasing a stove, which

was only within the reach of the wealthy in the 18th century. As a result,

stoves first became widely used, not in the home, but in public buildings such

as churches, shops, and schools.

After Independence Erie Canal system beginning in 1817 made

stove importation realistic. Prior to this improvement, the heavy cast iron

stoves either had to be produced locally or brought in by wagon from the east,

making them prohibitively expensive. In 1818 a Seneca Falls merchant advertised

in the Geneva Gazette, ten plate and Franklin stoves from the Constantia Iron Works on Oneida Lake , which were probably brought in by canal.

Beginning quite suddenly in September of 1823, several Geneva stores started

advertising stoves, among these Phineas Prouty’s offer of “Box, Oven, Cooking,

Parlor, and Franklin STOVES” at his Seneca Street store. This sudden change may

have coincided with the opening of the canal to Seneca

Lake . Most households still did not use stoves extensively, and

many houses, including the Prouty-Chew House (built in 1829) and Rose Hill

(1839), were constructed with fireplaces in nearly every room.

Prouty’s

stove advertisement from 1823 Geneva Gazette

Because

they were heavy and difficult to transport, stoves were often produced locally.

In 1837, Burrall & Dwight offered the Geneva Cooking Stove, patented by

Burrall (the Thomas Burrall who patented many agricultural tools). According to

the advertisement, this stove required “less fuel, and answers more purposes

with less labor, than any other Stove in use.” In 1846, an advertisement for

the Geneva Foundry Store offered a list of 10 different types of wood and coal

stoves in multiple sizes at wholesale and retail prices. Cooking and heating

stoves took off in the 1830s and 40s as fuel costs increased and transportation

networks improved. In November of 1850 Robert Swan’s mother writes Margaret, “We

got two very nice stoves for you & some Sundry useful things are put up

with the Stoves.” The stoves were shipped on the Erie Railroad, likely to Elmira and then on the Chemung

Canal and Seneca Lake to Geneva

Cookstove

in Rose Hill kitchen

As

technology improved, households adopted a variety of heating methods. Some

people preferred to use a fireplace in the parlor and put stoves in smaller,

less formal spaces. Manufacturers also produced fancy, decorated stoves for the

parlor, like the Andes line by Geneva

Rose

Hill main hall showing radiator on the rear right side

The

Prouty family put a wood burning fireplace in their 1858 bedroom addition, but

a coal grate in their new dining room in 1870. They also had a furnace as early

as 1857 that had to be started up when the cold weather came. You can see the

remnants of this system throughout the house today.

Furnace

grate in the Prouty-Chew House.

None of

these efforts succeeded in keeping them warm when the weather turned severe:

“And

today we're glad to keep our noses in doors, it is so bitterly cold. The

children wore blankets pinned over their heads for one hour this morning and

cried with the cold. Ally's cup of water by the bedside was frozen and Grandpa

has worn his overcoat all day. Tonight the wind howls in shrieks—the snow flies

in clouds, and the keen searching cold penetrates even our furnace-heated

rooms.” —Adelaide

Thermometer

5° below zero this morning & 30° in our room. We all had cold noses &

struggled very acutely. —Phineas Prouty, Jr., 1859

As

evidenced by the abundance of foundries producing boilers, heaters and stoves

in Geneva

For more

information on comfort and heat in homes, see:

Priscilla

Brewer, From Fireplace to Cookstove:

Technology and the Domestic Ideal in America Syracuse ,

NY : Syracuse

University

Elisabeth

Donaghy Garrett, At Home: The American Family, 1750-1870. New York

Backstory

with the American History Guys, website and podcast on heating and cooling

history: http://backstoryradio.org/climate-control-a-history-of-heating-and-cooling/