By Kerry Lippincott, Executive Director

(Warning – I’m not a military historian. What follows is my small attempt to commemorate the 150th Anniversary of Gettysburg and the role played by the 126th. For more information, I recommend Written in Blood: History of the 126th New York Infantry in the Civil War by Wayne Mahood and The Redemption of the Harper’s Ferry Cowards: The Story of the 11th and 126th New York State Volunteers Regiments at Gettysburg by RL Murray.)

Every family has that place where you visit on a regular

basis. It’s a place where even though

you know the lay of the land, you may still “discover” something new. For my family one of those places is Gettysburg .

In 1989 we made our first we made our first visit and over

the years we’ve been back too many times to count. While on our first visit, my brother Matt and

I actually thought that the body of Jenny Wade (the only civilian killed during

the battle) was in the basement of the Jenny Wade House. As our parents toured the house, Matt and I

stood at the basement’s entrance warning people not to go down. (Twenty-three years later I finally overcame

my fear and re-visited the house. And

yes, the “body” is still there). On

another visit Matt and Dad roamed Little Round Top looking for a marker for the

20th Maine

while Mom and I suggested that perhaps we all should stay on the nice trail created

by the National Park Service. Eventually they stumbled upon the statue of Joshua

Chamberlain. In 2008 I thoroughly

enjoyed the tour of the Shriver House as it tells a side of the Civil War that

often gets forgotten – the effects of a battle and its aftermath on civilians.

Last summer our “adventure” was searching for the 126th

New York

monument. My parents had read about the

regiment so they wanted to know where the monument was located. Whether we will

admit it or not, my family has a ritual at Gettysburg .

On our first night we simply drive around the battlefield. After a good thirty minutes or so, we found

the monument in Ziegler’s Grove on Hancock

Avenue . If

you are familiar with Gettysburg , the monument

is near the old Visitor

Center Geneva .

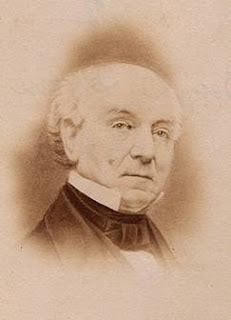

On June 15, 1862 the 126th New York Infantry

Regiment was organized in Geneva

by Eliakim Sherrill (who would become the regiment’s commanding officer). The regiment consisted of men from Ontario , Seneca and Yates Counties Geneva and

Rushville. During their first

engagement, the regiment surrendered to the Confederates at Harper’s Ferry earning

them the nickname “Harper’s Ferry Cowards.”

The regiment was quickly paroled and spent several months at Camp Douglas

in Chicago

waiting to be exchanged. It goes without

saying that the men of the 126th had something to prove and Gettysburg was their chance.

In late June 1863, the 126th was on garrison duty

around Washington , DC

when they were transferred to the Army of the Potomac . The regiment arrived in Gettysburg on the early morning of July 2

(the second day of the battle). For two

days, the regiment played an important role in defending the Union lines,

particularly during Pickett’s Charge. Of

the approximately 455 men from the 126th at Gettysburg , 40 were killed (including

Sherrill), 181 were wounded and 10 went missing. Only three other Union regiments had more men killed, wounded or

captured – 24th Michigan (272), 111th

New York (235) and 151st Pennsylvania (223). Three members of the regiments (George H

Dore, Morris Brown, Jr. and Johnny Wall) would receive Medals of Honor for

capturing Confederate flags.

For the next two years, the 126th fought in

battles in Virginia , including the Wilderness,

Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor and Petersburg . To honor the men of the 126th, the State of New York dedicated a monument at Gettysburg on October 3, 1888.