Robert Swan was born in

1826, the fifth child of New York City New York City

In 1848, he began his

study of farming at the age of 22, writing of his first day at the Johnston

On the 31st day of July 1848 I left home via Albany

His second day proved more

challenging:

Aug 3rd Thursday. I arrose [sic] this

morning at 5, dressed and went down to breakfast at six. After breakfast I went

to help thrash [sic] wheat in the upper barn this day we

did upward of Fifty Bushels, in an

hour which Mr J. said “was great work"

On the 7th he was still

threshing and "dirty as a sweep." The threshing continued until

August 14th, when they started ploughing for the planting of the next year's

crop of wheat.

|

| For several men to thresh 50 bushels of wheat in an hour, they were likely using a horse-powered machine, like this one. |

Robert's description of his days over the two years

that he lived at Johnston

Of course, as the son of a

wealthy man who was learning from, not working for Mr. Johnston, Robert did not

have to work in the same way that the paid farm laborers did. When he had

problems with his foot he was laid up for a couple of days, and when his family

came to town to visit he had the leisure to spend time with them. This would

not be an option for a man who only got paid when he worked, as was the case

with most farm laborers. Still, Robert was working hard and getting hands-on

experience with one of the best farmers in the state.

Robert's decision to take

up farming was apparently not unusual. At one point in his diary he writes: Nov 6th Monday. This morning I went over

to Geneva Johnston Seneca County Winterthur

Museum in Delaware Johnston

Robert Swan's professional

choice agreed with him: Sunday August

13th How unlike the City where all is confusion is the country where

every thing seems quiet thus quieting the heart of man. Based on his

writings and the letters of his family members, the Swans were well-off, but

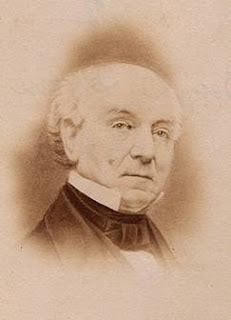

not ostentatious or overly concerned with society and station. Robert's father

Benjamin was very wealthy and prominent, but seems to have been mostly a

self-made man (if you take his son Fred's description literally, and that may

not be wise), whose primarily concerns were family and religious matters. He

took a genuine interest in the farm and was a life member of the New York State

Agricultural Society, watching Robert's progress in improving the farm every

summer when he and his wife came for a month-long visit.

Next time we'll look more

closely at how Robert Swan managed and farmed his own land at Rose Hill.