The Geneva

Why

is a flapper? [sic] Who knows? Well, why is she called a flapper? Now,

that's different. In . . . a story

published 12 years ago, Harry Leon Wilson . . . called the little dumpling girl

to whom ‘Our Hero, Bunker Bean,’ found himself married, the ‘flapper.’ . . . When asked recently why he called his

. . . girl a flapper, Mr. Wilson said he didn't exactly know. ‘I heard the term first in England

Or,

Yes,

many times we've wondered, why they call the young ladies flappers. In the spring time, summer time, and fall

there does not seem much reason for giving them this cognomen. . . . Then we saw how they wore their galoshes

[unbuckled and flapping]” (January 21, 1922).

Or,

Flappers Resembled Ducklings

The

term "flapper," as applied to young girls of a certain type, is not

modern, as most people suppose, but is really close on two centuries old. Early in the seventeen hundreds growing-up

girls were first called "flappers" from a fancied resemblance to the

young ducks, neither fledging nor grown-up, but dashing about with a good deal

of noise and flapping of wings” (July 28, 1922).

|

Singer and dancer Josephine Baker in a very

flapper-ish ensemble.

|

Wikipedia, however, suggests that

these theories were actually mistaken.

According to the article on Wikipedia, flapper was actually a slang word

in England England and the United States

By

1920, the term had taken on the meaning we associate with it today. As

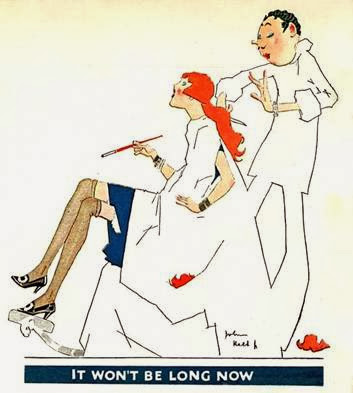

one critic put it, "the social butterfly type… the frivolous, scantily-clad, jazzing

flapper, irresponsible and undisciplined, to whom a dance, a new hat, or a man

with a car, were of more importance than the fate of nations” (Wikipedia article on the flapper). Clearly, not all

women in the 1920s were flappers. The

flapper followed the extremes of fashion and flouted convention. For example, Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby was a flapper.

|

| Boyshform elastic undergarment ad. |

The Daily Times talked a lot about flappers - most of the time, disparagingly. The paper recounts a story from

In June 1922, the Times reported:

Barbershop,

Once Haven for Man, Now Catering to Flapper Patrons

.

. . investigation by a Times reporter has disclosed that . . . the modern

flapper has invaded what was once . . .

a sanctuary for the male of the species alone – the barbershop. And the shops are cleaning house and

installing fancy window curtains in her honor.

She walks right in, so Geneva

The Times sometimes, though, tried to be even-handed: “THE

POOR FLAPPER . . . gets credit—or is it dis-credit—-for a lot of things for

which she really is not to blame. To be

true [sic] she allows only the lower buckle of her galoshes to have any

responsibility, but she didn't originate the style. It originated at Cornell” [February 28,

1922].

|

And sometimes, the paper reported

other voices in the debate:

“Bishop

Thomas F. Gailor . . . Says Woman of

Today Is No Different from the Woman of Grandmother’s Day

Though the debate continued, by the

mid-1930s flapper was outmoded slang. It

may be that in the depths of the Great Depression, other worries took precedence.

Do you

enjoy this 1920s moment? The Geneva

Historical Society is hosting several workshops and programs in December and

January about the 1920s all leading up to our Speakeasy Party at Belhurst on Friday,

January 17. For more information about

the Speakeasy or related programs, call us at 789-5151 or go to www.genevahistoricalsociety.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment